Hi everyone,

Should older workers systematically be paid more than younger ones? Tough question, right? 🤔 This debate isn’t new but it’s increasingly relevant in today’s rapidly changing work environment.

On the one hand, seniority pay systems reward experience and loyalty, reflecting the belief that seasoned workers bring knowledge and skills that create value. On the other hand, these systems can stifle innovation, discourage mobility, and perpetuate age-based inequalities in both directions—young workers may feel undercompensated for their contributions, while older workers can face unemployment because they are seen as too expensive.

Here are some thoughts on how precarious work arrangements, digital transformation, and shifting employment practices make this question more pressing: so, should seniority be a criterion for pay?👇

No. Seniority-based pay is a waste of talent and a barrier to innovation.

Seniority-based pay systems can stifle talent. In many industries, young workers—despite being innovative and highly productive—are paid significantly less simply because they lack seniority. This creates a sense of unfairness. In many sectors, younger workers experience frustration with compensation systems that seem to reward tenure over results. This can lead to disengagement and turnover.

Also, seniority pay systems can discriminate against older workers too when they are deemed too expensive. In France, older workers face higher unemployment rates (and they remain unemployed for longer) partly due to perceived higher costs.

In the public sector, civil servants enjoy the comfort of seniority-based pay, which constitutes a barrier to exit. For example, many French teachers feel trapped in jobs they no longer enjoy but can’t leave because seniority dictates their pay (many fear they wouldn’t be paid as much doing something else). This creates a phenomenon often referred to as job lock where workers are financially tied to positions they no longer find fulfilling. So seniority pay creates a disincentive for mobility and creativity because people are made to think of their jobs as golden handcuffs. They are bored and they bore other people out!

In a way, I was only able to leave teaching 10 years ago because I lacked seniority and was paid poorly. I had nothing to lose. I could change careers without a financial hit. And yes, I had mixed feelings (I’ll admit, even some resentment) about the fact that my older colleagues were paid much more than I was for doing the same job, simply because they had seniority.

Yes. Experience and knowledge do have real value.

Many organisations have learned the hard way that experience can be invaluable. A classic example is Boeing’s decision over a decade ago to lay off thousands of older, experienced workers as part of a cost-cutting effort. By replacing these veterans with less expensive, less experienced workers (including contractors), Boeing saw a significant decline in product quality, including serious quality control issues in the production of the 737 aircraft.

👉 Also read: 5 things I find very interesting about the Boeing downfall. Laetitia@Work #70

Little by little, ageism has made many companies become blind to the productivity boost that experience does provide, especially in industries where process knowledge is critical (like aerospace, law or healthcare, for example). They fail to grasp how costly the retirement of highly experienced workers is for them. The savings made by cutting senior salaries do not outweigh the cost of losing institutional memory and facing a shortage of specialised skills. Retaining experienced employees should be a priority!

It actually depends on how work is organised and which skills are valued.

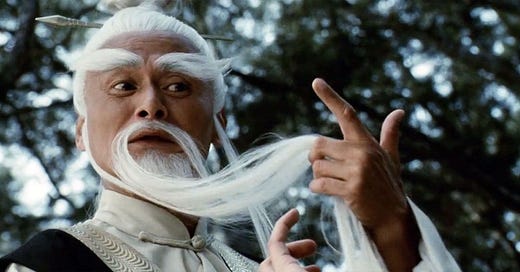

In traditional craft industries (like carpentry or cuisine), experience and seniority are highly valued because mastery of the craft takes a lot of time. For example, in Japanese manufacturing, senpai (senior workers) are often responsible for mentoring kohai (younger workers), passing down not just technical skills but also deep process knowledge, a practice that is considered crucial to maintaining high standards.

By contrast, in Fordist systems of mass production workers are considered interchangeable. Henry Ford famously said, "the man who places the part does not fasten it," highlighting how workers were limited to repetitive tasks, making seniority irrelevant. Indeed, if anybody can do these repetitive tasks, what’s the point of seniority?

Unlike the Fordist system, lean manufacturing systems like Toyotism, which became dominant in the latter half of the 20th century, heavily value seniority. Experienced workers are seen as integral to continuous improvement processes, or kaizen, where their deep process knowledge helps identify and eliminate inefficiencies. Also seniority systems were designed to enhance loyalty and reduce turnover:

Toyota needed to get the most out of its human resources over a forty-year period—that is, from the time new workers entered the company, which in Japan is generally between the ages of eighteen and twenty-two, until they reached retirement at age sixty. So it made sense to continuously enhance the workers’ skills and to gain the benefit of their knowledge and experience as well as their brawn. (...)

Remember that Ford’s system assumed that assembly-line workers would perform one or two simple tasks, repetitively and, Ford hoped, without complaint. (The Machine that Changed the World, James P. Womack, Daniel T. Jones, and Daniel Roos).

Today, the rapid pace of technological and cultural change places greater emphasis on youth. Young workers are perceived as more adept at handling digital transitions, and their lack of ingrained habits makes them seem more adaptable to disruptive innovations. Thus organisations pretend to prioritise younger talent for their technological fluency and willingness to experiment.

AI tools can enhance the productivity and skills of less experienced workers, enabling them to perform tasks that previously required years of expertise. This creates a perception among companies that senior workers, with their higher salaries, are less essential, as AI can seemingly compensate for a lack of experience. However, much like the pitfalls of Fordist mass production, where interchangeable, unqualified workers led to quality issues, relying solely on AI-driven labour can result in problems of judgment, oversight, and subtlety. Senior employees—those "senpai"—bring deep institutional knowledge, problem-solving abilities, and leadership that AI cannot replicate. Companies that dismiss the value of experience in favour of AI-driven efficiency risk undermining long-term quality and sustainability.

Perhaps the modern-day Toyota System will emerge from learning the right combination between the experience of the senpai and the power of AI…

Seniority-based pay is now increasingly challenged.

While seniority pay remains prevalent in the public sector, many workers in precarious jobs—freelancers, contractors, gig economy workers—are excluded from its benefits. A majority of today’s global workforce is in some type of informal or non-standard employment, i.e. these workers typically do not experience the upward pay trajectory that seniority-based systems offer. For them, pay is often determined by market rates and immediate performance rather than accumulated experience.

This creates a dual reality. Insiders, often in stable, unionised jobs, benefit from seniority-based pay. Meanwhile, outsiders, who change jobs more frequently or work on short-term contracts, never achieve the benefits of tenure. In the EU, for example, workers on fixed-term contracts tend to earn 15% less on average than their permanent counterparts. The same trend is evident in the US, where suppliers, contractors, freelancers and gig economy workers often earn less than their full-time, “traditional” counterparts with similar levels of experience.

More employees are stepping out of the workforce mid-career, shifting across industries or embracing contingent work and other nontraditional employment models at some point in their careers. A 2022 LinkedIn survey of 23,000 workers found that 62% had already taken a career break and 35% would potentially take one in the future. Workers are also contending with involuntary disruption to their careers due to economic cycles, caregiving responsibilities, displacement during conflict and natural disasters, and shifting responsibilities as technology and business models evolve.

As atypical career paths become mainstream, the well-entrenched stereotypes that underpin most talent management strategies will prove a growing barrier to talent acquisition and retention. (Harvard Business Review)

Conclusion

In a world where careers are increasingly fragmented and non-standard work is on the rise, we risk losing the value that seniority brings to the table. Experience, accumulated over time, deserves recognition beyond market fluctuations and short-term performance metrics. Can we still ensure that those who commit their life to a craft aren't left behind in the name of cost-cutting and flexibility? If not, will people still commit to a craft in the future? And can we learn to value experience acquired outside a craft or industry?

🚀 📣 🗓 With “Vieilles en Puissance” we are organising a roundtable discussion and an “apéro” on September 25 at La cité audacieuse in Paris. One can't talk about women's money without talking about age: the older we get, the more the wealth gender gap increases.

👉 If you are in Paris, come on September 25 for a roundtable and a drink! 🍷

💡Check out the latest articles I wrote for Welcome to the Jungle: Age does matter, at work and in the White House (in English), « L'âge compte, au travail comme à Matignon et à la Maison Blanche », Avons-nous tant à craindre de l’américanisation du marché du travail ?, Bravo et merci : comment développer une culture de la reconnaissance dans sa boîte ? (in French).

🏆 By the way, I am quite proud to announce that the number of my publications on Welcome to the Jungle has now reached 300!! (It took quite a few years to get to this number!)

🎙️ There is one new Nouveau Départ episode! Les batailles de la natalité (with Julien Damon) 🎧 (in 🇫🇷). Subscribe to receive our future podcasts directly in your inbox!

Miscellaneous

👶 Parents Should Ignore Their Children More Often, Darby Saxbe, The New York Times, September 2024: “The modern style of parenting is not just exhausting for adults; it is also based on assumptions about what children need to thrive that are not supported by evidence from our evolutionary past. For most of human history, people had lots of kids, and children hung out in intergenerational social groups in which they were not heavily supervised. Your average benign-neglect day care is probably closer to the historical experience of child care than that of a kid who spends the day alone with a doting parent.”

I hope you gain more wisdom as well as wealth as you age! 🤗

Really interesting article Laetitia. I think we do need to think differently about ways to keep older people in the workplace but perhaps its on a downslope. Many older workers are also past the years when life costs are highest. Less convinced that pay by seniority curtails innovation. Intuitively it feels like it would have the opposite effect. Frustrated younger workers simply leave and set up new business based on new ideas.

Also interest in how these dynamics affect women through their careers?