Hi everyone,

I have a confession to make: I used to hate bureaucracy. Like many of us, I rolled my eyes at endless forms, cursed slow administrative processes, and grumbled about "paper pushers" who seemed to make life unnecessarily complicated. I often joined the age-old chorus of people mocking bureaucrats and their rules.

But I was wrong. Today, as our world faces threats from autocratic leaders and billionaires who want to bypass rules for their own gain, I’m having a big change of heart. I love bureaucrats. I love technocrats. Give me a thousand bureaucrats over one autocrat any day.

It struck me recently when Bernard Arnault, France’s wealthiest man and a titan of the luxury industry, criticized Brussels’ “bureaucrats”. Like many billionaires, he's frustrated with the bureaucrats who might actually enforce tax regulations and prevent the ultra-wealthy from paying zero taxes. Meanwhile, former President Trump aims to purge the civil service of anyone who isn't loyal to him personally, and Elon Musk fantasises about dismantling regulations with chainsaws.

This made me realise that bureaucracy isn't just about paperwork – it's about protecting all of us from the whims of powerful individuals who think they're above the rules.💡👇

How we got here: a brief history

Throughout most of human history, power worked through "patrimonialism" (see Rita McGrath’s newsletter on the subject) – a system where leaders ruled based on personal relationships and favours. Kings, emperors, and local lords made decisions based on what benefited them and their allies, not on consistent rules or fairness.

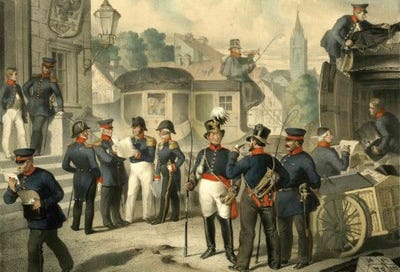

Over time, as the limitations of these systems became evident, a shift unfolded gradually, here and there, towards more stable and effective forms of governance. 18th-century Prussia is a case in point.

In this relatively small and resource-constrained state surrounded by more powerful rivals like Austria and France, in order to survive and compete, Prussian leaders realised they needed a more efficient and predictable way of governing than relying on aristocratic privilege or personal networks. So they began to build a professional civil service founded on meritocratic principles. Officials were selected based on their qualifications, trained systematically, and expected to follow codified procedures. This approach aimed to ensure consistency, competence, and accountability in the administration of the state.

The Prussian model marked a real turning point in the way societies thought about governance. For the first time, power wasn’t supposed to depend on who you knew, your family name, or your place in the social hierarchy—it was supposed to follow rules, procedures, and clear lines of responsibility. Of course, it wasn’t perfect, and it certainly wasn’t inclusive (you still had to be male, educated, and from the right background), but it planted the seed of something new: a vision of government that could be fairer, more consistent, and focused on serving the public. That idea—that officials should be trained, competent, and committed to a sense of duty—spread beyond Prussia and inspired reforms in countries looking to modernise their institutions. It was a big step away from the unpredictability of royal whims or feudal loyalties and toward something more stable and structured—an approach that made more sense in a world growing ever more complex.

This shift didn’t go unnoticed. Max Weber, the brooding German sociologist, saw just how profound it was. He argued that bureaucracy wasn’t just a practical fix for messy governance—it was one of the defining traits of modern life. For Weber, it represented a move from power rooted in tradition or personality to something more rational and rules-based. Bureaucracy, in his view, made power more accountable and less arbitrary. It helped the state move beyond the narrow interests of rulers and begin (at least in theory) to serve society as a whole.

The criticism: a history of frustration

Of course, bureaucracy has its problems. Franz Kafka's novel The Trial gave us an enduring image of faceless systems crushing individuals. These systems, designed for consistency and control, can end up treating people as interchangeable parts—disregarding their specific circumstances, needs, or humanity. By the late 20th century, complaints about bureaucracy became universal – from Ronald Reagan's quips about government to David Graeber's critique of "bullshit jobs." We've all felt the frustration of being caught in administrative loops or facing seemingly senseless requirements.

Today's populists have cleverly turned bureaucracy into a scapegoat, presenting it as the ultimate villain responsible for society's ills. In movements like Brexit, the "faceless bureaucrats" in Brussels were portrayed as out-of-touch elites, imposing rules that undermined national sovereignty and common sense. Leaders like Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson capitalised on this, framing European Union regulations and the so-called "technocrats" as distant, unaccountable forces that meddled in the daily lives of ordinary people (supposedly fussing over useless stuff like the precise curvature of bananas, the size of fish, or the colour of olive oil labels). This critique resonates strongly with those who feel disempowered by systems they don't understand or can't navigate.

Silicon Valley's critique of bureaucracy took a different form, presenting itself as a utopia of innovation, where "seamless" services and minimal regulation were the keys to success (actually, we need some friction). Entrepreneurs in the Valley frequently decried bureaucracy as an obstacle to progress, claiming that red tape stifled creativity and slowed down new ventures. However, this rhetoric often masked a deeper libertarian agenda: the desire to operate with few, if any, regulations, allowing companies to exploit workers, bypass environmental protections, and avoid paying their fair share of taxes. In reality, the disdain for bureaucracy was less about fostering innovation and more about creating an environment where these tech giants could thrive without the constraints that traditional regulations impose, turning them into unregulated predators in the market.

Much of all this criticism stems from a fundamental misunderstanding of, or disregard for, what bureaucracy protects us from.

Why we need bureaucracy now more than ever

In our current moment, with authoritarian tendencies rising globally, bureaucracy serves as a vital safeguard for democracy.

#1 Equality before the law: When billionaires like Arnault complain about bureaucratic delays, they're really complaining that they can't use their wealth to bypass rules that apply to everyone else. Bureaucracy ensures that whether you're applying for a permit, filing taxes, or seeking environmental approval, you face the same requirements as everyone else. This is not a bug – it's a feature.

#2 Protection against arbitrary power: Trump's dream of staffing the government only with loyalists reveals exactly why civil service protections exist. Career bureaucrats – from FDA scientists to forest rangers – provide continuity and expertise regardless of who wins elections. They're the ones who prevented many of Trump's most dangerous impulses during his first term.

#3 Institutional memory: When disasters strike or crises emerge, bureaucracies remember how similar situations were handled before. They maintain records, preserve knowledge, and ensure that society doesn't have to reinvent the wheel with each new administration. The weakening of critical agencies like FEMA could lead to a dangerous lack of preparedness, as institutional memory is eroded and vital lessons from past crises are lost.

#4 Slowing down bad ideas: Yes, bureaucracy is slow. But when someone proposes something reckless – like imposing tariffs without understanding economic consequences – that slowness becomes a virtue. Bureaucratic processes force decision-makers to consider implications, gather data, and consult experts.

#5 Creating public goods: From food safety to air traffic control, from pension systems to pandemic response, bureaucracies create and maintain the public goods that markets alone cannot provide. They ensure that profit motives don't override public welfare.

Bureaucrats are not obstacles – they're guardians. The civil servant who insists on proper documentation isn't being difficult; they're ensuring accountability. The regulator who demands environmental impact studies isn't stifling innovation; they're protecting our shared future.

When I hear complaints about "Brussels bureaucrats," I think of the officials who ensure that products sold across Europe meet safety standards, that workers have rights, and that competition remains fair. When people mock the "deep state," I think of career professionals who kept critical systems running even when political leadership failed.

There's something beautiful about a system where power is constrained by rules, where processes exist to ensure fairness, and where dedicated professionals work quietly to make society function. In an age of strongmen and tech billionaires who believe their wealth puts them above the law, bureaucracy represents something precious: the idea that we're all subject to the same rules.

In a world where autocrats and oligarchs constantly push for fewer constraints on their power, I'll take a slow-moving, rule-bound bureaucracy over their vision of unchecked authority any day.

My thoughts are with all the bureaucrats who have been mistreated, sidelined, disrespected, or laid off by the likes of Musk and Trump—the Social Security worker on whom the elderly depend, the National Parks official who safeguards natural heritage, the IRS employee who tracks down fraud, and countless others quietly upholding the public good behind the scenes.

Trump—and many populist governments elsewhere—would rather see tomorrow’s few bureaucrats (like Musk’s “kids”) focus solely on gatekeeping welfare systems, obsessively checking that the poor aren’t getting “more than they deserve.” In doing so, they not only punish the vulnerable but also ensure that bureaucrats are seen not as protectors of the public good, but as petty enforcers of a system rigged against the poor. Besides persecuting the poor, bureaucracy isn’t required in a regime where there are no rules, only access.

So here's to the good old bureaucrats – the unsung heroes who file the reports, check the boxes, and ensure that the machinery of civilisation keeps running 🦸♀️🦸♀️🦸♀️ In these uncertain times, they may be our best defence against those who would rule by decree rather than law. I never thought I'd say this, but: I love bureaucracy, and you should too.

💡For Nouveau Départ, I wrote many new articles (in French):

🎙️ And I recorded this podcast with Caroline Loisel: Naviguer en incertitude, survivre dans le flou

→ Subscribe to receive my future podcasts and articles directly in your inbox!

✨ Event in Paris. Join us for the first edition of VIVAGEN on April 29th at Adobe, Paris 16th! 🌍✨ I’ll be speaking alongside Celica Thellier, co-founder of ChooseMyCompany, about how we can foster intergenerational collaboration in the workplace. We’ll dive into creating environments where people of all ages thrive, with less focus on generational stereotypes 💬🤝 It’s time to rethink how we value the work of individuals, regardless of age, and design workplaces that last. Don’t miss it! 🎤

🔗 Discover the program here: vivagen.org

Miscellaneous

🤯 Buried by Bots: How AI is Maxing Out Your Cognitive Bandwidth, Matteo Cellini, Work 3 - The Future of Work (Substack), April 2025: “AI is meant to be a super helper. It promises to make things easy. Do the boring stuff. Let you think about what really matters. Is that true, though? Does it always feel easier? Or is it just… different work? First, we need to understand what Cognitive Load is. Think of it as your brain's working memory, its active RAM. It's the mental effort required to learn something new, solve a problem, or simply process the information hitting you right now. Like computer RAM, it's limited. When overloaded, our focus frays, decision-making suffers, mistakes creep in, and burnout looms. The way tasks are structured, information is presented, and tools are designed drastically impacts this load.”

Learn to appreciate the bureaucrats around you! 🙏🙏🙏

Hello Laetitia,

I wonder if by bureaucracy you meant "civil service."

The Egyptian pharaohs, Louis XI (who invented the Post Office), Louis XIV (and Colbert) already had public administrations. But the number of officials was too small for bureaucratic excesses to ruin the country's life.

The Soviet Union was an expert in bureaucracy, which didn't really protect citizens from the excesses of the prince. And which really made daily life miserable.

David Graeber wrote that the source of bureaucracy was capitalism (we're allowed to disagree).

In short, I don't think bureaucracy is linked to a political regime. Nor that it protects citizens from the excesses of the powerful.

Civil services, on the other hand, ensure equal treatment among citizens, provided the country isn't too corrupt.

But bureaucracy remains an evil that affects both public services and businesses.