Dignity is what matters, but what is it exactly?

Laetitia@Work #6

Hi everyone,

I love the word dignity, I love pronouncing it and it makes me emotional because it makes me think about what it means to be human. Work and dignity are words that are supposed to be related somehow. But how? Can you have dignity without sufficient money? Is dignity a product of work or is it something you must have in work?

Dignity is defined (by the Oxford dictionary) as “the state or quality of being worthy of honour or respect”, which involves both the respect of others and self-respect. It’s also described as an inalienable right for all people to be respected for their own sake, to be treated ethically, which in theory you can have without work.

When we speak of dignity, there’s also a constant threat looming: it’s something you can be deprived of, or something you can lose. If you’re mistreated, if you’re a slave, or if you do something that you believe has no value, you are deprived of it. There are so many ways work in one form of other can take your dignity away from you.

We intuitively know that dignity is about feeling needed by others and having a place in society. That’s why work and dignity have long been associated. In fact, when it comes to work, dignity is one of two things that really matter. I’d like to use today’s newsletter to reflect upon the relationship between work and dignity and how you can find dignity at work. Read on.

Stability and dignity

In an inspiring TED discussion titled “How do we find dignity at work?”, venture capitalist and future of work expert Roy Bahat explains that most of the current discussions about the future of work are besides the point. After talking to a lot of workers across the US, he understood that when it comes to work, there are two main themes that actually matter to people: stability and dignity.

“If you survey people and ask them what they want at work, for everybody that makes less than $150,000 a year, they’ll take a more stable and secure income on average over earning more money”. A stable income is what makes it possible to plan your life, pay your bills, live a decent life and have a tomorrow. It doesn’t mean money doesn’t matter, far from it, but when you’re not rich, stable incomes do make your life slightly easier.

As for the second theme, dignity, Bahat admits it’s a tricky concept: “That concept of dignity. It’s difficult to get your hands around it.” Obviously dignity doesn’t put food on the table, so stability comes first. But stability without dignity isn’t enough. There are two meanings attached to the concept: the feeling of being worthy and the feeling of being part of something greater than yourself. Worthiness and a place in society. Existing as an individual AND as a full member of the group. Often discussions about “meaning” at work focus too much on the “individual” part of it, but without the collective, there can be no dignity.

I must say I found the video too short and was left a bit frustrated. How do you find dignity at work? For Bahat like for many Silicon Valley thinkers the main solution is universal basic income, so human activities and economic security can be separated and people can be free to find dignity in looking after their loved ones or doing what they love and not worry about paying the rent. But is that really it? Is there no way to find dignity at work and be paid for your work?

It got me thinking about bullshit jobs and vocations. Anthropologist David Graeber explains provocatively in his book Bullshit Jobs: A Theory, that when it comes to jobs, social value and pay are inversely correlated. Because virtue should be its own reward. These arguments have been made again and again about teachers: “One wouldn’t want people motivated primarily by greed to be teaching children.” There is so much dignity in working as a teacher, and you want money too?

And so our world confuses price and value. As a teacher (which I was for 8 years), I did have some sense of self-worth because I felt useful and was good at my job. But I did not feel respected and valued by others (outside the classroom). I can’t say I enjoyed the full dignity spectrum. It’s not easy to feel good about yourself when you’re told you are a “cost” to society and when your (low) salary signals what is seen as your (low) economic worth. Vocations have infinite value, they say. But they’re priced low.

This is why, unless we do away completely with money and salaries (for everyone), I don’t see how we can separate dignity and pay, i.e. have jobs that supposedly come with dignity but no money. UBS doesn’t solve everything. We live in a world where value is priced. Low price equals low value equals low self-worth. For more dignity we also need more collective bargaining, more balanced power relations, and stronger public services that assign value where value is due. We also need to be able to find dignity in work. So let’s try to dig a little further...

The Declaration of Philadelphia

We owe our current definition of work and all the institutions supporting and surrounding it (our social protection, school systems, banking credit, etc) to the 20th century. Modern work is what forms our social and cultural fabric, and our life expectations. So I won’t attempt to give you a large historic overview of how work and dignity are related, but will merely stick to recent history. For French Professor Alain Supiot, an expert on work and dignity in the 20th century, the most foundational document on the matter is the so-called “Declaration of Philadelphia”.

Before the end of the second world war (1944), the International Labour Organisation (ILO) laid out a complete “social bill of rights” that marked the expansion of welfare states and a framework for future labour relations. The Declaration of Philadelphia sought to fit an age of “new aspirations aroused by the hopes for a better world”. Let’s put it this way: the 1930s and the war had provided painful lessons of in-dignity and the “new aspirations” were about never living these lessons again. The main idea underlying this declaration was that there should be no work without dignity, and to make that possible social values must be upheld.

Let’s look at some of the words used in the declaration, which focuses on a set of principles to guide the action of the ILO:

Labour is not a commodity.

Freedom of expression and of association are essential to sustained progress.

All human beings, irrespective of race, creed or sex, have the right to pursue both their material well-being and their spiritual development in conditions of freedom and dignity, of economic security and equal opportunity.

[The text also mentions the goal of furthering] the employment of workers in the occupations in which they can have the satisfaction of giving the fullest measure of their skill and attainments and make their greatest contribution to the common wellbeing.

Supiot mentions this declaration over and over again in his works (most notably in a book translated into English, titled The Spirit of Philadelphia: Social Justice vs. the Total Market) because he believes the set of principles listed in it has been compromised profoundly by market values. Little by little what he calls the “Total Market” has replaced the declaration’s ideal of social justice. And that leaves little room for dignity.

“The staggering growth of inequalities, the hollowing out of the middle classes, now facing utter precariousness, and the mass migrations of people driven out of their homes by misery or ecological devastation [as well as] the anger and the multiple forms of violence that fuel ethno-nationalism and xenophobia” are evidence that dignity is very much under threat.

There are three things at the heart of the Philadelphia declaration that I believe are a good start to begin to grasp the concept of dignity at work: 1. Economic security, 2. Labour is not a commodity and 3. Work should enable you to give the full measure of your skill and make the greatest contribution to the common wellbeing.

Dignity in work vs dignity through work

Oops. Did you read what I just wrote? The second and the third element listed above seem to be totally incompatible with scientific management and the industrial paradigm in which workers are “resources” (commodities) that should be as interchangeable as possible. It’s incompatible with the division of labour that deprives workers of the ability to “give the full measure of their skill”. It’s incompatible with bullshit jobs. Can you have dignity when you’re an employee and you are a “human resource”?

The difficulty of reconciling the elements listed in the Declaration of Philadelphia with 20th-century salaried work is so tricky, that we’ve been convinced we need to distinguish between dignity in work and dignity through work. Dignity in work is said to be reserved to the few artists, craftspeople, researchers, independent thinkers, and other workers with vocations who can find it in what they do. But pretty much everyone else must do with dignity through work, i.e. their work is not necessarily worthy, but they make a living that enables them to have a decent, dignified life. They fit in the group. They have a place in society. They have stability and agency. And that’s good enough for them.

Call me an idealist but I believe dignity through work is now a fallacy. And scientific management has lived. We’ve organised all jobs, including in proximity services, around division of labour and subordination. But today for lack of sufficient tradeoffs we need to rethink the Fordist deal whereby workers were commodities. It was somewhat acceptable to be a “commodity” in exchange for a good share of the wealth created and a whole bundle of benefits. With the unbundling of jobs, we should turn to the values of craftsmanship—autonomy, responsibility, creativity—to help restore dignity in all work.

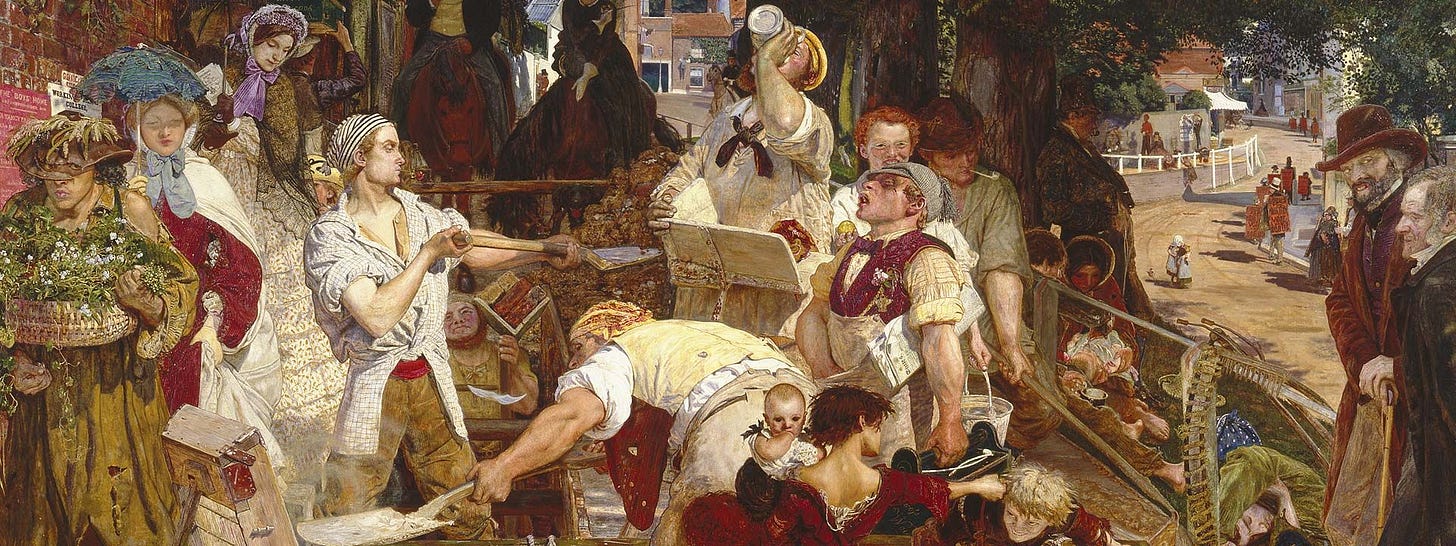

In my book Du Labeur à l’ouvrage, I make the case that the ideas behind the Arts and Crafts movement could inspire us to rethink work today. William Morris, the movement’s main thinker and artist, was convinced that craftsmanship was indeed the only way to restore the workers’ lost dignity. For him, it is by making things both beautiful and useful that workers can express their uniqueness and find meaning at work. Craftsmanship is the only way out of alienation. And it can apply to lots of different jobs (including the job of cleaning, for example). Craftsmanship is the anti-industrial way of organising work and it could find renewed relevance today.

So, to sum up (honestly I found this theme super hard to write about!), dignity is a feeling of being worthy and having a place in society. Without stability, dignity isn’t much (because you can’t eat it). In theory worthiness does not require paid work: you can have dignity without work. But work is so omnipresent in our lives and shapes so many of our institutions that it’s good to think of dignity and work together. Here are the elements I would list to answer the question “how do you find dignity at work?”:

- Stability is so essential that it should come first. It involves sufficient, regular incomes, but also a solid safety net so you can have a dignified life (healthcare, pensions, social insurance…).

- When labour is a commodity and you have a hyper-specialised, repetitive job, there is no dignity in work, which was acceptable when stability came with the job: you could then find dignity through work, i.e. you could buy your dignity with work.

- Alas in today’s context of a relative absence of stability, dignity and work are hard to reconcile. If dignity through work is a fallacy, then we need to turn again to dignity in work. And the values of craftsmanship are where we should start.

A few weeks ago, I was in Geneva with friends Ben Robinson and Dan Colceriu from Aperture Hub and we recorded this podcast: "Future of Work: From Graft to Craft".

New Welcome to the Jungle ebook about scaling culture: “Comment faire évoluer sa culture quand l’entreprise grandit ?” (in French). (The English version will be published by next week and will be featured in next week’s newsletter!).

We’re all biased! New episode in English : “When the solution makes the problem worse: discover the ‘cobra effect’” ; and a new one in French about the Hawthorne effect: “Comment l’effet Hawthorne améliore la productivité de vos équipes”.

I’ll be in Paris on Thursday (February 6) for a conference “Qui travaillera demain ?” with Le Monde, Courrier International, and The Camp at La Gaîté Lyrique at 5pm.

Content related to this week’s newsletter:

🗞️ “The future of work is in proximity services … but first we need to speak about work and gender”, Medium, October 2019.

🗞️ “Back to Craftsmanship: Lessons from The Arts and Crafts Movement”, Medium, June 2017.

🗞️ “Why Taylorism Cannot Apply to the Cleaning Craft”, Medium, October 2017.

🗞️ “The Unbundling of Jobs and What it Means for the Future of Work”, Medium, May 2018.

🗞️ Welcome to the Jungle “must-read” article about David Graeber’s Bullshit Jobs a Theory.

🗞️ Welcome to the Jungle “must-read” article about Alain Supiot’s Le travail n’est pas une marchandise (French only).

🗞️ ILO Declaration of Philadelphia (1944).

🎥 “How Do We Find Dignity At Work?”, Roy Bahat and Bryn Freedman, TED Salons, November 2018.

🗞️ “Hedge: Inventing A New Safety Net”, Nicolas Colin, Medium, January 2019.

🗞️ “Enough With This Basic Income Bullshit”, Nicolas Colin, The Family Papers, September 2016.

Miscellaneous

🗞️ “Better Work in the Gig Economy”: New Doteveryone research (January 2020) shares the stories of gig workers for whom “the app has become a trap”, and calls for policy change and platform redesign that champion three pillars of better work: financial security, dignity, dreams.

🗞️ “Further Exploration Needed in Women”—the Hidden Sexism in Scientific Research”, Sarah E. Hill, Behavioral Scientist, December 2019: “Females continue to be understudied in all phases of research, including pre-clinical research on non-human animals and cells.”

🗞️ “Angels’ in Hell: The Culture of Misogyny Inside Victoria’s Secret”, J. Silver-Greenberg, K. Rosman, S. Maheshwari & J. B. Stewart, New York Times, February 2020: is it a surprise that Victoria’s Secret was a sexual predators’ lair? No. But #metoo in the world of lingerie comes with good news: this culture of sexism is also causing the brand’s demise as fewer women want to buy from them.

⚕️Akesio: my friend Dr Lavinia Ionita launched her startup to help people and companies fight stress. Discover the Akesio blog here!

That’s all for this week. I wish you all lots and lots of dignity 🤗